Please enjoy this (comparatively) low consequence, old school blogpost about Andy Warhol.

In college, I took a class called “Sociology of the 1960s”. As you can imagine I immediately became enthralled with Warhol. I watched Factory Girl approximately 100 times because messy Sienna Miller movies are important. A tip is to pair it with a room full of people drinking Franzia from the box!

Warhol was a speck of chaos in an era of chaos. He scammed scammers and I still can’t fathom he was serious. (This is why I only lasted a single semester as an art major. Also because I could not draw a chair). The art world is wild — the bad and the good!

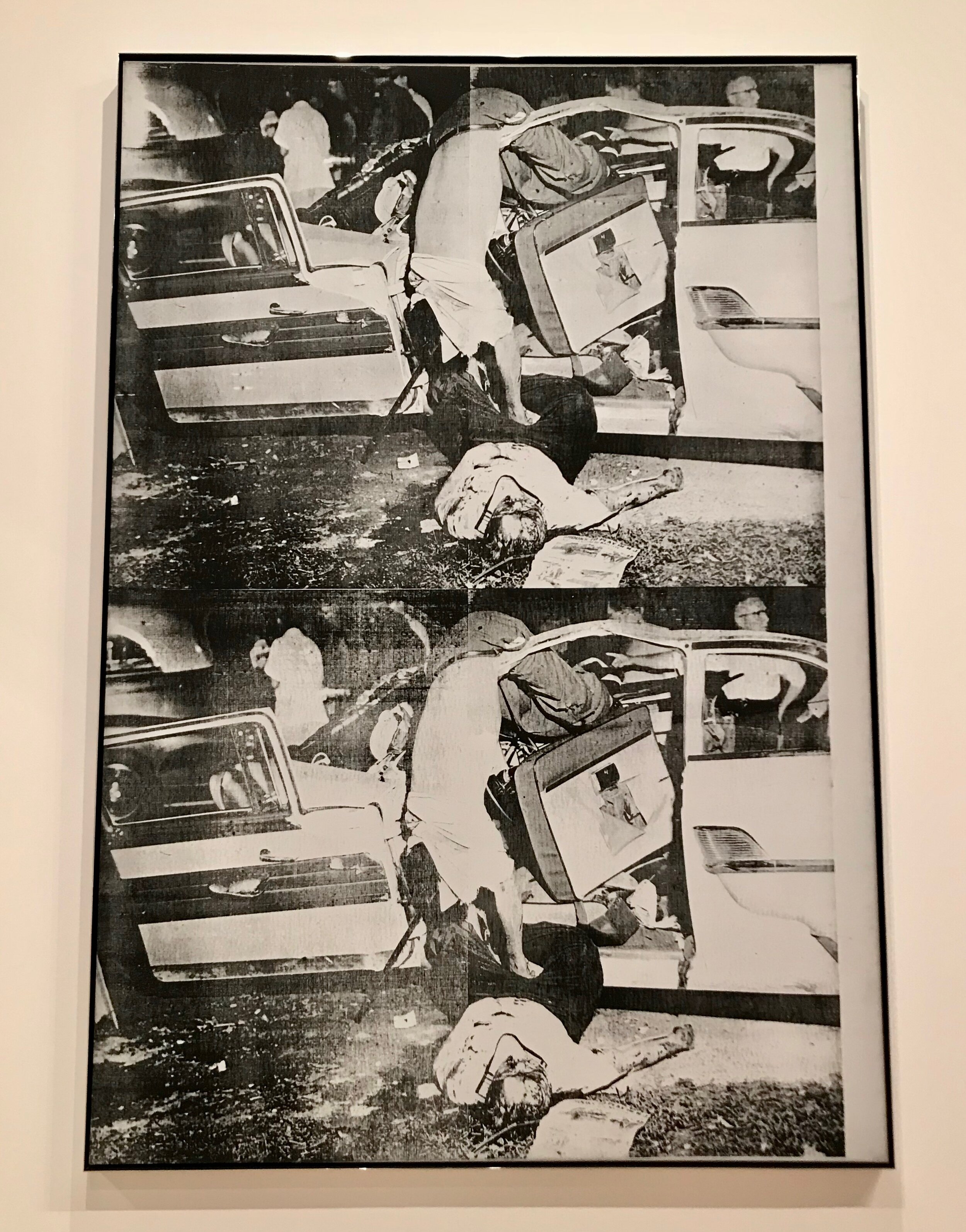

Around this time I found a book about Warhol’s “death and disaster” series. That’s right, kids. It’s not all Brillo boxes and Marylin.

This discovery coincided with a time when I was living in New Orleans and immersed in Katrina recovery. The coast was drenched in oil and the death toll in Haiti was incomprehensible. I was processing and art seemed a useful tool to do so.

Through the years I’ve made a point of stopping into museums to see his various works. From Austin to Venice, (even Fargo!) I’ve checked piece by piece off my list.

Then, in the year 2018, Edie Sedgwick herself called down from Heaven and told The Whitney it was time — they would do a Warhol exhibit and feature works from his Death & Disaster series.

I went to New York this spring and as I wandered among the death & disaster pieces I had nothing but questions.

Me, a person with questions.

Warhol interpreted disasters as the replication of a single person’s death. It was through an individual death that he attempted to capture the magnitude of collective death. You know, the Stalin quote.

“I thought that people should think about them sometime. The girl who jumped off the Empire State Building. Or the ladies who ate the poisoned tuna fish and the people getting killed in car crashes. It’s not that I feel sorry for them. It’s just that people go by and it doesn’t really matter to them that someone unknown was killed. So I thought it would be nice for these unknown people to be remembered by those who ordinarily wouldn’t think of them.”

Hardin, an art person, claims Warhol “tries to mask death’s reality” in an effort to unravel “the postmodern denial” of death as real. He continues on to say, “If we look at art, we can see how American popular culture uses simulated death as a means to efface it. Andy Warhol exploits this fascination with death by aesthetisizing, multiplying, discoloring, and obscuring numerous representations of death and disaster—such as his Car Crashes series—and in doing so, exposes the superficiality of death and disaster in American popular culture.”

It’s All-American violence.

In the span of two years (1962-63) Warhol created the majority of pieces for his Death and Disaster series. He interpreted death and disaster as an extension of American consumerism. The exemplary is the direct contradiction between the tuna fish and Campbell’s soup cans: death and comfort. Death and disaster are consumed in tabloid magazines and discussed, mundanely, on the radio. They are both a feature and a function of capitalism.

It is certainly telling that the artist who described America in the twentieth century included disasters in his definition of pop culture. He was right to include it. His work revolved around subjects (celebrities/ household items) that were ubiquitous– which of course includes death and disaster. Yet, this subsection of his work that dealt in death and disasters is not well known. The warm images of Campbell Soup cans are remembered over the Tuna Fish cans. I reflected as I walked through the Whitney, that the disaster pieces were kept isolated in three rooms. The pieces were made more palatable sandwiched between Flowers and The Last Supper. The crowds were biggest in the portrait room.

Their relative absence in the remembering of his work is especially telling when you consider how many death and disaster pieces he made. When Rainer Crone cataloged Warhol’s work he found as many as 150 of 650 pieces could be categorized within the Death and Disaster designation. Considering the proportion of pieces on this subject, some like Walter Hopps, have argued the subject was clearly a serious preoccupation of Warhols’. (When you wonder why I haven’t published a journal article this year please know that many art books had to be read for me to write this paragraph with confidence. I had to Interlibrary Loan multiple books.)

In obscuring the details of the images Warhol also abstracts the cause of death. For someone who argues he is giving the victims the recognition their mundane deaths would not have otherwise received, he does nothing to tell the story of the individual. Instead, he focuses only on their moment of death. In this way, these photos align with those who die during true disasters. Communities that are affected by disaster remain largely invisible until the crisis. Then attention centers around getting a confirmed number of the dead. Not much more.

Desensitization to individual death is not removed from our desensitization of disasters.

“It was Christmas or Labor Day – a holiday – and every time you turned on the radio they said something like, ‘4 million are going to die.’ That started it.”

I wonder about this feeling of increasing death in the context of the climate crisis and our ability to communicate death as a threat and consequence. Jarring death tolls in the age of climate change feel inevitable despite the many possibilities of prevention.

An art person would say that he “the extra panel was added to push the pieces further into the abstract”. Sure, but also… as we reinterpret this series in the era of climate change we are reminded that death, mundane or otherwise, is all around us. There is comfort in the repetition. When death comes repeatedly from the same source, the predictability allows us to prevent those deaths. That blank canvas may hold the space for what Warhol deems inevitable deaths but I, a person not usually known for optimism, might say that half remains blank as those future deaths are prevented.

I’ll admit that I left the Whitney slightly disappointed. Some iconic disaster pieces were missing from the collection. I was, however, consoled by the fellow museum-goer who resembled Warhol himself. Was this performance art, fangirling, or coincidence!?

Unexpectedly, my dance with Warhol didn’t end in New York City but rather the itty bitty town of Stykkishólmur, Iceland.

This summer, standing in a two-room Volcano Art Museum I look over to see, with no warning, one of Warhol’s Vesuvius prints. It was one of the pieces I felt was missing from the Whitney’s collection. (If I’m honest, when I arrived in New York to find none had been included I threw a fit. The nerve of its absence!)

I had been wanting to see one for 10 years, I had no idea it would be there — there was much gasping.

Vesuvius was the last I felt compelled to see for myself.

I’m ready to leave Warhol in the past and follow around the new climate artists who help us understand the death and disaster around us.

I’ll just go watch Factory Girl one more time…